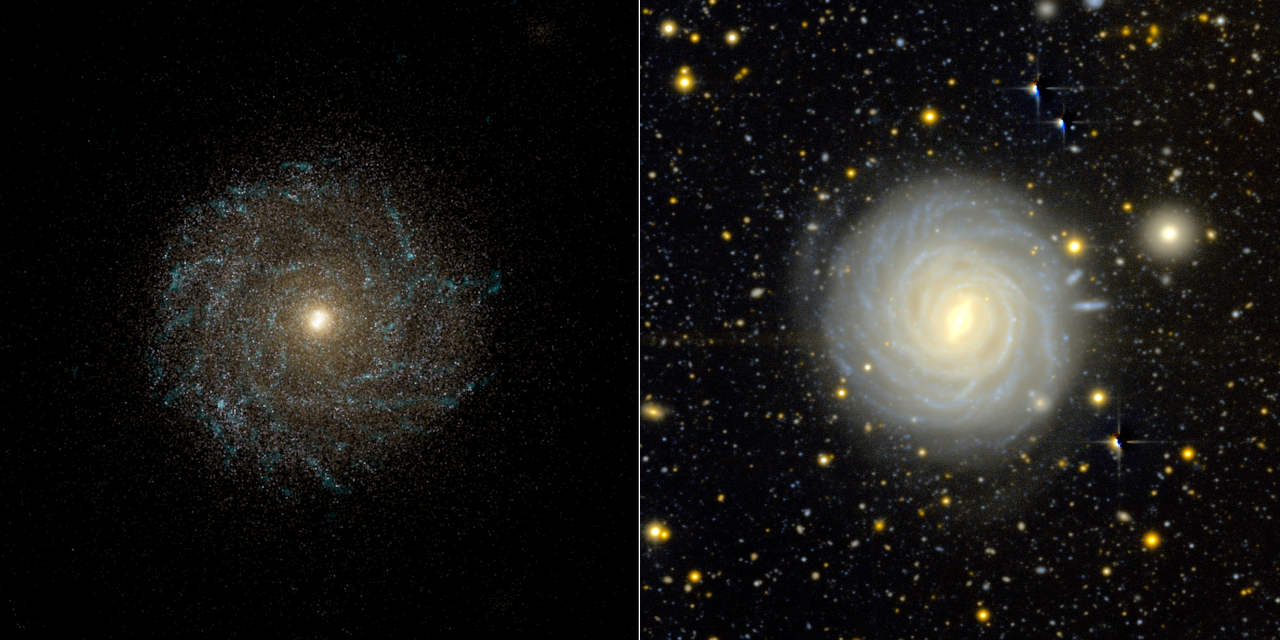

In the standard cosmological model (𝜦CDM), galaxies are merely the visible "tips of the icebergs," residing within massive, invisible cocoons of dark matter known as haloes. While these haloes dictate the evolution and motion of galaxies, measuring their true size and mass has long been one of the most challenging tasks in astrophysics.

A new study published in Astronomy & Astrophysics by Claudio Dalla Vecchia and Ignacio Trujillo from the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias (IAC) proposes a breakthrough: a physically motivated definition of a galaxy’s edge that acts as a precision "ruler" for the dark matter surrounding it.

For decades, astronomers have relied on the "effective radius" (Re)—the radius containing half of a galaxy's light—as the standard measure of size. However, Re is often a poor proxy for a galaxy’s physical boundary. Because stars can migrate inward or outward over billions of years, and because Re is sensitive to the brightness of a galaxy’s core, it does not correlate strongly with the underlying dark matter structure.

"The traditional way we measure galaxies is like trying to guess the size of a mountain by looking only at the brightness of the ski resort on its peak," explains the research context. The result is a high degree of statistical "noise," making it difficult to link visible stellar structures to the vast dark matter haloes that contain them.

The researchers focused on a newer metric called R1. This is defined as the radial distance from the center of a galaxy where the stellar mass surface density drops to 1 M☉pc-2 (one solar mass per square parsec). Unlike the effective radius, R1 is tied to the fundamental physics of star formation. Theoretical models suggest that gas only becomes dense enough to form stars (the transition to molecular hydrogen) above a certain threshold. R1 represents the "fossil record" of this threshold—the outermost limit where the galaxy was ever able to form stars in situ.

To test if R1 could reveal the properties of dark matter, the team utilized the EAGLE (Evolution and Assembly of GaLaxies and their Environments) simulations. These are massive, high-resolution cosmological models that track the interaction of gas, stars, and dark matter across billions of years of cosmic history.

The findings were striking:

- Extreme Precision: The relationship between a galaxy’s stellar mass and its R1 size showed an intrinsic scatter of only 0.06 dex. This is significantly tighter than any previous mass-size relation.

- The Halo Connection: The study established a direct, double power-law correlation between the galaxy size (R1) and the halo size R200—the radius at which the halo density is 200 times the critical density of the universe).

- Six Times More Accurate: By using R1, the researchers could estimate the mass of a dark matter halo with six times greater precision than by using the traditional effective radius.

For physicists and cosmologists, this "ruler" is a game-changer. Dark matter cannot be seen directly; it is typically inferred through gravitational lensing (the bending of light) or galaxy dynamics (measuring the speed of rotating stars). Both methods are observationally expensive and require massive amounts of telescope time.

The R1 method allows researchers to estimate the properties of the invisible halo simply by taking a deep image of the galaxy and measuring its outer stellar edge.

This discovery provides a new tool to test the 𝜦CDM model. If observations of real galaxies continue to match these simulation results, it confirms our understanding of how baryonic matter (atoms) and dark matter interact to build the large-scale structure of the universe. If they diverge, it could point toward "new physics" in the dark matter sector.

"We have found that the edge of the visible galaxy is not arbitrary," the study suggests. "It is a precise gateway to the dark side of the universe."